By the middle of the century, almost 70% of humanity will live in cities. This is where the battle for the mental health of future generations will be decided, warns the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), the largest organization of psychiatrists in Europe. Its experts, including researchers from Wrocław Medical University, have recently published a position paper aimed at setting the direction for research and health policy in this area.

The EPA emphasizes that urbanization brings both risks – such as noise, pollution, and social isolation – and enormous potential. Cities can become spaces for promoting mental health if urban planning, social policy, and modern technologies are incorporated into activities aimed at the wellbeing of residents. This is a crucial voice in the European debate, as the EPA, representing over 80 national psychiatric associations and thousands of doctors, sets standards of care and co-creates public health policies across the continent.

The dark side of urbanization

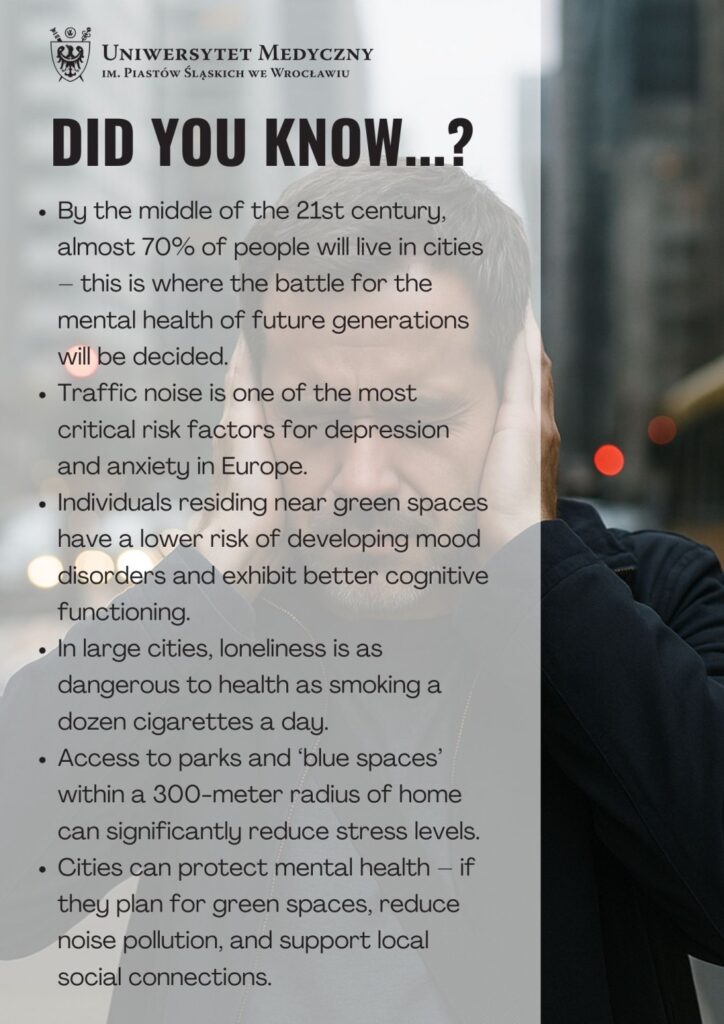

The authors of the position paper point out that rapid urban development contributes to the emergence of risk factors:

- stimulus overload – traffic noise, air pollution, light at night,

- overcrowding and poor housing conditions,

- poverty and social inequalities, particularly evident in large conurbations,

- violence, homelessness, and addiction, which are on the rise in some parts of cities,

- feelings of loneliness, despite being surrounded by thousands of people.

All these phenomena can increase the risk of depression, anxiety disorders, psychosis, and even suicide attempts.

“Our position shows that both risk and protective factors affect mental health in cities. The most important risks include noise, air and light pollution, lack of greenery, overcrowding, social inequalities, and feelings of isolation,” emphasizes Julia Karska, M.D. from Wroclaw Medical University “That is why it is important to minimize exposure to noise and smog in everyday life, seek contact with greenery and real neighborly bonds, and take advantage of available forms of mental health support. Importantly, cities can mitigate these risks by planning green spaces, providing safe and accessible transportation, and integrating mental health services with primary care. This is not only a problem for individuals, but also a task for urban planning, public health, and local communities.”

“Szymon Kowalski, M.D. points out that four problems are particularly evident in Polish cities: “Firstly, traffic noise – on a European scale, this is a significant risk factor for depression and anxiety. Secondly, there is limited access to green spaces within a 300-meter radius. Research has shown that contact with nature reduces stress and the risk of mood disorders. Another problem is loneliness and social fragmentation, and finally, economic and housing tensions – rental instability, overcrowding, and debt, which directly translate into a deterioration in mental health.”

Opportunities offered by the city

However, the city is not only about threats. It is also a space for creating modern solutions in mental health care. The authors emphasise the potential of:

- community building – local initiatives that create bonds and counteract loneliness.

- health-promoting urban planning – access to green spaces, safe neighborhoods, efficient transport,

- digital technologies – teleconsultations, mental health support apps, including those based on artificial intelligence,

- social policy – integration programs for migrants, support for people in crisis, community services,

“There is a lot of good to be done if the city consciously initiates it,’”says Julia Karska, M.D. “Firstly, services – easier access to assistance, including digital tools. Secondly, space – parks, green and blue corridors, peaceful walking and cycling routes. Thirdly, community programs that facilitate real contact and involve residents in co-deciding about space. Examples from Helsinki, Rotterdam, and Stockholm show that a city that protects wellbeing is possible and profitable.”

The need for a new perspective

According to the authors, it is necessary to move away from the simple division: ‘the city harms – the countryside protects’. The reality is much more complex. Different social groups – from children to older people, from migrants to LGBTQ+ people – experience the impact of city life differently. Therefore, policies and actions tailored to local realities and needs are needed.

““We recommend that local governments treat mental wellbeing as a planning parameter – with measurable standards such as access to green spaces within 300 meters, noise reduction and housing policies that reduce overcrowding,” adds Szymon Kowalski, M.D. “It is also important to develop local support centers for vulnerable groups, including new residents and migrants. These are measures that have a real impact on health and reduce social costs.”

Conclusions for the future

Urbanization is an irreversible process. Therefore, as EPA experts emphasize, cities must become spaces that support mental health, not just economic centers of development. In practice, this means integrating psychiatry with urban planning, social policy, and digital technologies.

This material is based on article:

Urban mental health: a position paper of the European Psychiatric Association

Authors: Błażej Misiak, Julia Karska, Kowalski Szymon, Courtet Philippe, Volpe Umberto, Meryam Schouler-Ocak, Destoop Marianne, Kristina Dr. Adorjan, Fabian Kraxner, MD, Victor J.A. Buwalda, Campion Jonathan, Julian Beezhold, Peter Falkai, Geert Dom

European Psychiatry, 2025