Wooden stakes for piercing the heart, iron nails, exorcism accessories, and other tools once believed to ward off dark forces—these are all part of a new acquisition by WMU. Dating back to the first half of the 20th century, a so-called vampire-neutralisation kit has been on display since January at the Museum of Forensic Medicine at Wroclaw Medical University.

Artifacts associated with vampirism gained popularity in Europe particularly after the publication of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), though such beliefs existed even earlier. A second wave of fascination emerged in the 1950s, driven in part by the rapid development of cinema. Most so-called “original” anti-vampire kits date from this period and were often assembled using pre-war artifacts. Today, many replicas are produced, loosely inspired by historical sets.

“The peak of interest in vampire folklore occurred between 1900 and 1920, and again in the 1950s—although the vampire motif is experiencing yet another revival in contemporary cinema,”

explains Dr Jędrzej Siuta from the Department of Forensic Medicine at Wroclaw Medical University and curator of the Museum of Forensic Medicine.

“Portable anti-vampire kits were particularly popular at the time. They were sold in suitcases, chests, or—as in our case—violin cases, allowing easy transport and rapid action wherever a body was located. Most of these items were produced in Germany. The set acquired for our museum, however, is of Polish origin and therefore unique. While the vast majority of such kits were never used in practice, what matters most to us is that its contents perfectly capture the spirit of the era and reflect the most widespread folk beliefs about beings thought to feed on human blood after death.”

What’s Inside the Anti-Vampire Kit?

The set includes, among other items:

- a collection of crosses,

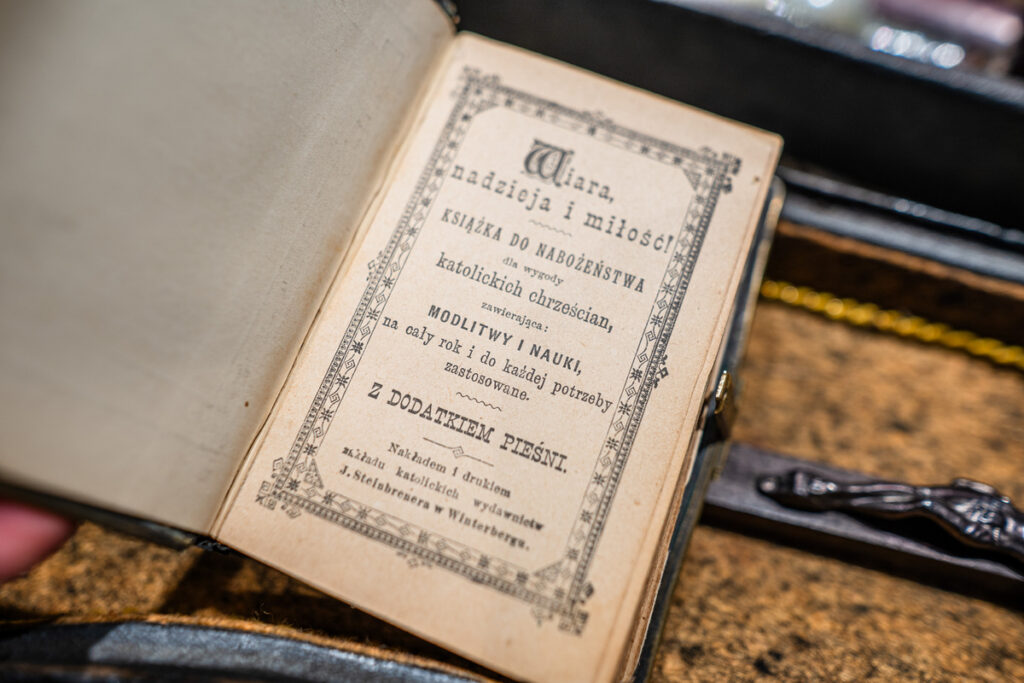

- a prayer book,

- a candlestick,

- silver-plated knives,

- a mirror,

- wooden stakes with metal tips used to pierce the heart or skull,

- nails likely intended to secure coffin lids.

There are also two small bottles—one for holy water and another containing traces of an unidentified liquid, which scientists from the Department of Forensic Medicine plan to analyse. A medallion found in the case will also undergo scientific examination. The kit additionally contains deer antlers, as the deer was once regarded as a noble animal symbolising the forces of good.

“Silver was commonly used in the fight against vampires, as folk belief held that evil forces feared it,”

says Dr Siuta. “Interestingly, this has a kind of medical justification due to silver’s antibacterial properties. Vampires were blamed for spreading plagues, and when a particular household escaped an epidemic, people searched for explanations. Silver objects—and garlic, which acts like a natural antibiotic—were thought to offer protection.”

Folk Rituals and Modern Forensic Perspectives

According to historical accounts, the hearts of alleged vampires were pierced with wooden stakes (often made of aspen or other hard wood) or iron rods. Sometimes skulls were perforated between the eyes, stones or bricks were placed in the mouth, or the head was severed and positioned between the legs. There was a whole spectrum of such rituals. From today’s perspective, a forensic pathologist would classify these practices as desecration of human remains.

In folk belief—later popularised by modern culture—a vampire was a “living corpse” whose powers had to be neutralised. Some individuals were suspected of vampirism even while alive, especially those who were ill, visibly deformed, suffered from abnormal sensitivity to light, or had unusual eye coloration. Nevertheless, ritual actions were typically performed only after death.

Extraordinary events following a person’s death—such as outbreaks of disease or mass livestock deaths—were also interpreted as proof of vampirism. Graves were then reopened, and a “professional” was called in.

“Sometimes, opening the grave revealed what was considered irrefutable evidence of vampirism: a lack of decomposition,” explains Dr Siuta. “In reality, this can occur under specific natural conditions, entirely unrelated to supernatural forces. All of these phenomena have scientific explanations.”

These include:

- Natural mummification, caused by rapid dehydration in dry, well-ventilated environments,

- Bog preservation (peat bog transformation), where the chemical composition of peat inhibits microbial activity,

- Adipocere formation, in which body fats transform into a waxy, soap-like substance under moist, oxygen-poor conditions, preserving tissue shape.

Examples of all these processes can be found among the exhibits at the Museum of Forensic Medicine.

Not Hunting Vampires—Explaining Them

“We won’t be hunting vampires,” assures Dr Siuta. “This kit, which has enriched the Museum of Forensic Medicine’s collection, will serve as a starting point for discussions about historical folk beliefs, so-called vampire burials, and broader issues related to forensic medicine. It will also be an object of scientific research—because it still holds more than one secret.”

Photo: Tomasz Modrzejewski